A Tragic Prelude: A Fight For A Free State

When the U.S. Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the United States was in a bitter argument over the legitimacy of slavery. The new act allowed territories to decide for themselves, through popular vote, whether they would be a free state or a slave state when they entered the Union.

Under the terms of the act, two territories were to be formed, Kansas and Nebraska. One would presumably become a slave state and the other a free state. Popular sovereignty would prevail and it was assumed that slave-owning Southerners would occupy Kansas and make it a slave state, while free state advocates would settle Nebraska. Things worked out as anticipated in Nebraska, but not in Kansas.

Influential outsiders decided to make an example of Kansas. Abolitionists in the North organized and funded several thousand settlers to move to Kansas and presumably vote later to make it a free state. The most notable of these organizations was the Emigrant Aid Company of Massachusetts, which helped to establish antislavery settlements in Topeka and Lawrence.

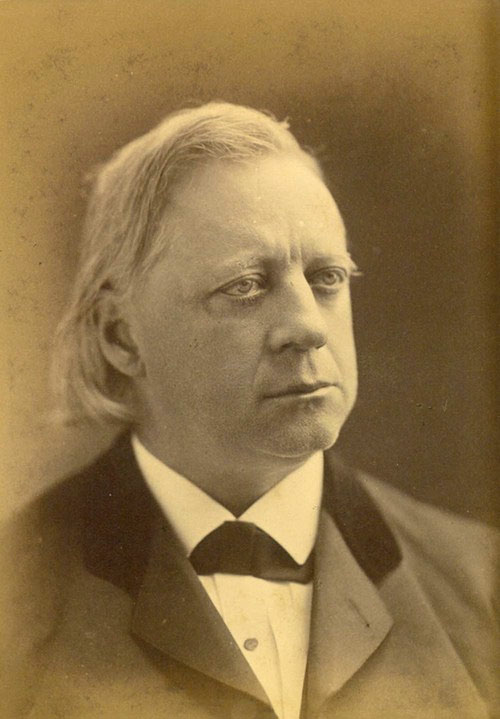

The abolitionist preacher, Henry Ward Beecher, collected funds to arm like-minded settlers (the precision rifles were known as “Beecher’s Bibles"). Fewer Southerners showed interest in settling in Kansas, but proslavery communities were formed at Leavenworth and Atchison.

Henry Ward Beecher

Territorial elections were held in 1854 and 1855, in which the proslavery forces won, largely through the violence and intimidation of the so-called “Border Ruffians." These were Missourans sympathetic to slavery who crossed the border into Kansas to stuff the ballot boxes. In some districts the number of ballots counted was twice the number of registered voters.

Few of the Border Ruffians actually owned slaves since they were too poor. However, they hated the Yankees and abolitionists and were unhappy with the prospect of free blacks living in neighboring areas.

Following the elections, a territorial legislature convened and promptly expelled all of the antislavery delegates, then enacted a series of proslavery laws. Meanwhile, an opposition government was created by free-soil forces in Topeka in late 1855. President Franklin Pierce recognized the proslavery government and ignored the one in Topeka.

The free-soil settlers were not necessarily abolitionists. Most were farmers who opposed slavery because the institution brought with it the plantation system. A replication of the cotton belt economy in Kansas would drive out the small homesteaders. The free-soilers loved their lands more than they cared about the plight of the slaves.

Hoping to induce the citizens of slaveholding states to emigrate to Kansas, the Lafayette (Missouri) Emigration Society appealed to their sense of Southern loyalty:

"Up to this time, the border counties of Missouri have upheld and maintained the rights and interest of the South in this struggle, unassisted and unsuccessfully. But the Abolitionists, staking their all upon the Kansas issue, and hesitating at no means, fair or foul, are moving heaven and earth to render that beautiful territory not only a free state, so-calloed, but a den of Negro thieves and "higher law" incendiaries."

This tense situation erupted into violence through two dramatic events that are often regarded as the opening shots of the Civil War:

- The Raid on Lawrence, Kansas. In May 1856, a band of Border Ruffians crossed the border from Missouri and attacked the free-soil community of Lawrence, looting and burning a number of buildings. Only one person was killed (one of the Ruffians), but the door to violence had been breached.

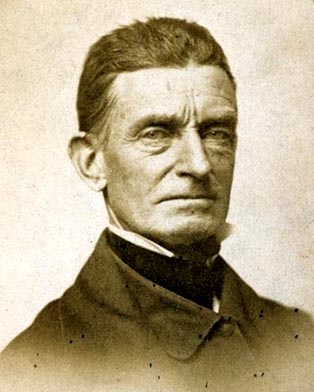

- The Pottawatomie Creek Massacre. A few days later, in retaliation for the Lawrence raid, abolitionist forces under the zealot John Brown attacked a small proslavery settlement on Pottawatomie Creek. On Brown’s orders, five men were executed with a scythe.

John Brown

The so-called "Border War" lasted for another four months until a new governor, John W. Geary, managed to prevail upon the Missourans to return home in late 1856. A fragile peace followed, but violent outbreaks continued intermittently for several more years.

National reaction to the events in Kansas demonstrated how deeply divided the country had become. The Border Ruffians were widely applauded in the South, even though their actions had cost the lives of numerous people. In the North the murders committed by Brown and his followers were ignored by most and lauded by a few.

In 1857, a Kansas constitutional convention was convened, which drafted a pro-slavery document. Antislavery forces boycotted the ratification vote because it failed to offer them a means to vote against slavery.

The dubious approval of the Lecompton Constitution did not deter President James Buchanan, who urged acceptance and statehood. Congress balked and ordered another election. This time the proslavery forces boycotted the process, allowing the antislavery forces to claim victory by defeating the document.

Both sides had resorted to fraud and violence, but it was clear the prevailing sentiment in Kansas was antislavery. In mid-1859, a new constitution was drafted which reflected that view and was approved by the electorate by a 2-to-1 margin. Kansas entered the Union as a free state in January 1861.

Explore Topeka's Bleeding Kansas History below:

The Historic Ritchie House

1116 S.E. Madison St.

(785) 234-6097

This two-story stone house served as John and Mary Ritchie’s house after they moved to Topeka in 1855 to fight against the expansion of slavery. Mr. Ritchie, who rode with a free-state militia, turned his property into a safe-haven for slaves fleeing north as part of the Underground Railroad. Following the Civil War, Ritchie allowed African Americans to settle on his land in an area of Topeka later to be known as “Ritchie’s Addition” and eventually a school for the settlers was built on Ritchie land. The Ritchies also donated the land that is now the Washburn University campus. That institution was founded by staunch abolitionists.

Constitution Hall and The Topeka Constitution

429 S. Kansas Ave.

www.kansasconstituionhall.org

After what is widely considered a corrupt election in March 1855, A pro-slavery government was created in Lecompton, Kansas. Fearful that the state might enter the Union as a slave state, anti-slavery supporters gathered in Topeka, in a building now known as Constitution Hall, to draft an anti-slavery constitution for the Kansas territory. For three weeks, 47 delegates from around the state gathered in Constitution Hall and wrote the first of four constitutions for the Kansas territory. Though the constitution was eventually blocked, the building continued as headquarters for the free-state movement, being used as a meeting hall, warehouse for weapons and supplies and as base for the Topeka guard, which protected free-state supporters.

Tragic Prelude

915 S.W. Jackson St.

(785) 296-3966

www.kshs.org/capitol

John Brown, an abolitionist from Ohio, came to the Kansas territory with five of his sons to fight against slavery. Brown believed the only way to absolve the land of the sins of slavery was to wash it away with blood. After a pro-slavery raid in Lawrence, where buildings and houses were burned and looted, Brown and a small group of men led an attack against five pro-slavery men at Pottawatomie Creek, killing them all. Brown led several more attacks against pro-slavery supporters while also helping freed slaves make it to safe territory. After leaving Kansas to try and rally African Americans to the cause, Brown attacked the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in what is now West Virginia. Brown was caught and eventually hanged. After his death, Brown inspired many more Northerners to join the cause, which eventually led to the Civil War. On the second floor in the Kansas State Capitol, you can find Brown immortalized in the mural Tragic Prelude by John Steuart Curry. Curry depicted the passionate abolitionist as larger-than-life, with a Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other, arms out wide protecting those behind him.